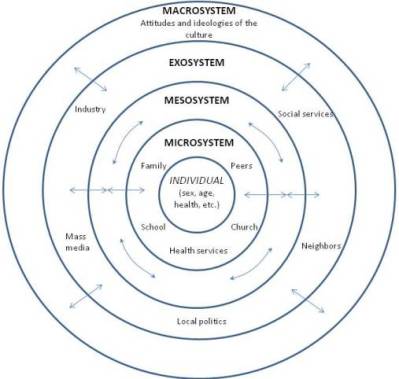

What does it mean to be vulnerable? The word vulnerability describes an individual or a group of individuals at risk for poor physical, psychological, and social health as a result of barriers experienced by social, economical, political, and environmental resources (Bruskas, 2008). Vulnerable populations include; ethnic minorities, gender, social support, education level, income, genetic predisposition, and age such as children and seniors. As our communities grow, all vulnerable populations should be a priority for our healthcare system. Nonetheless, there is one population that is growing rapidly and requires immediate attention, our elderly population. Over the past 40 years, the proportion of senior population has grown from 8% to 14% in Canada. According to demographic projections, the proportion of seniors is expected to increase rapidly to between 23-25% of the total population by 2036 (Statistics Canada, 2018). What does this mean for the future of our healthcare system?

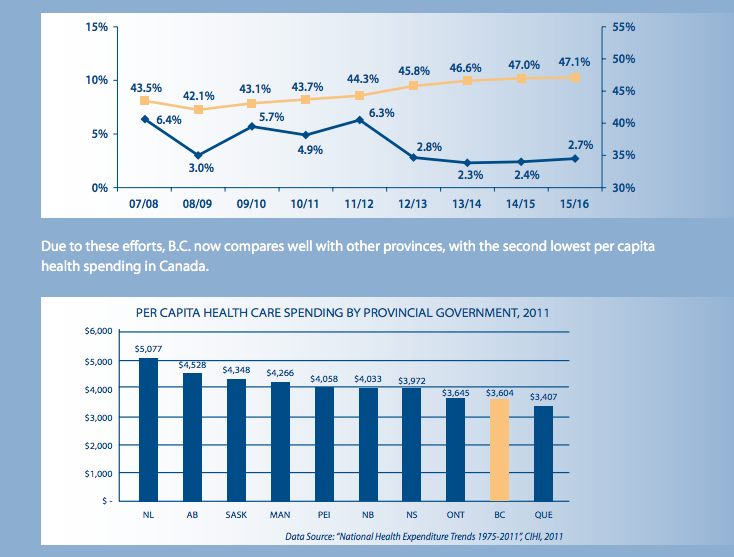

Currently Canadians over age 65 consume roughly 44% of provincial and territorial health care budgets, and the governments are concerned about the health care system’s capacity to provide quality of services in the future (The Canadian Medical Association, 2013). Although age does not automatically mean ill health or disability, the risk of both does increase with age. Age-related risk factors that influence one’s health include; decreased mobility, increased chronic disease, increased nutritional needs, financial decline related to retirement, and social isolation (Potter & Perry, 2001). Statistics Canada confirms that nearly three-quarters of Canadians over 65 years have at least one chronic health condition (The Canadian Medical Association, 2013). Statistics Canada also indicates that the Canadian healthcare system lacks resources to help older adults cope with these age-related risks. While these risk factors can have major affects on one’s quality of life, many of them can be managed and prevented. The key to providing optimal care for older adults begins with recognizing the risk factors then tailoring healthcare and educational programs towards this population (The Canadian Medical Association, 2013). I believe that in order to provide optimal care and support for Canada’s aging population, while trying to minimize pressure on the health-care system, governments at all levels should invest in programs to promote healthy ageing. As well, a comprehensive continuum of health services to provide optimal care and support.

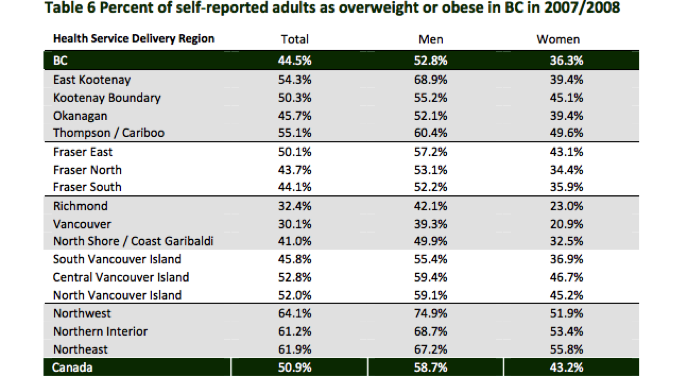

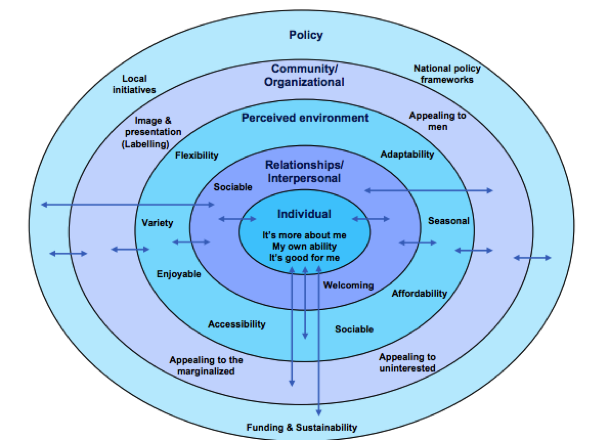

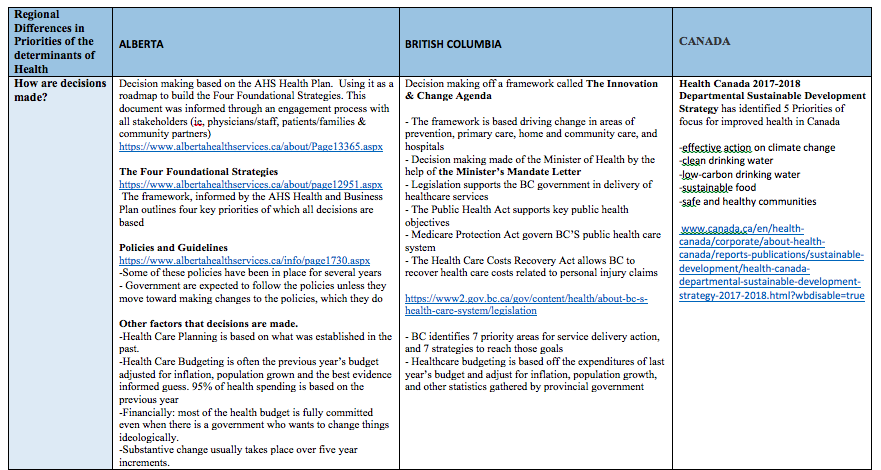

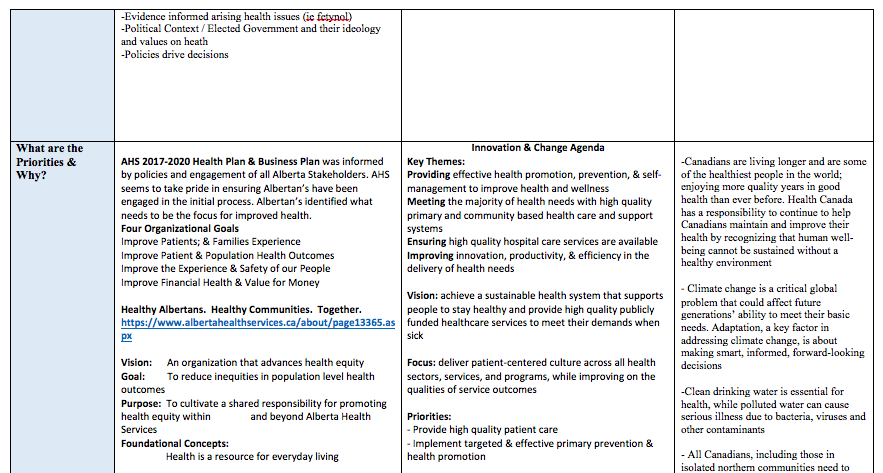

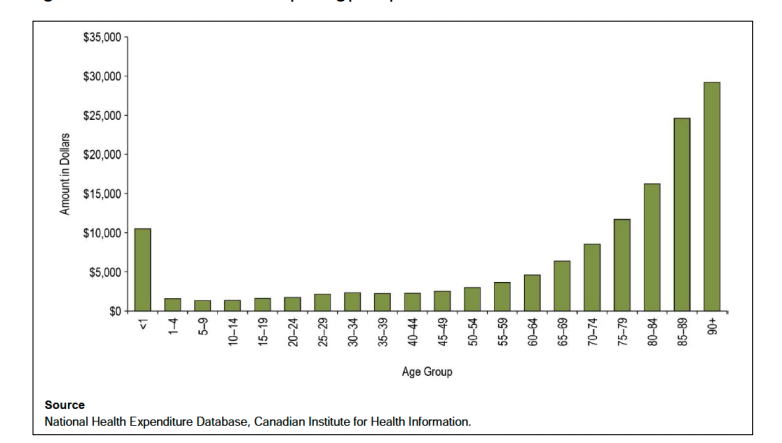

Figure 1. Canada’s National Expenditures on Health in 2012 for each of the age groups. Retrieved from https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/policy-research/CMA_Policy_Health_and_Health_Care_for_an_Aging-Population_PD14-03-e.pdf

The Public Health Agency of Canada defines healthy ageing as a process of optimizing opportunities for physical, social, and mental health to enable seniors to take an active part in society and enjoy their lives (EuroHealthNet, 2018). It is understood that initiatives to promote healthy ageing will help lower the healthcare costs by reducing the number of hospital and physician visits due to disability and chronic disease (EuroHealthNet, 2018). Programs focused on physical activity, nutrition, and mental health will have a profound effect on individual quality of life, social support, physical health, and mental well-being. Despite the inevitable declines associated with age, research suggests the way in which older adults spent their final years, either in a nursing home, or living independently, may be greatly influenced by their physical activity habits throughout their life (Krucoff, Carson, Peterson, Shipp, & Krucoff, 2010). Participation in a regular physical activity is an effective way to reduce/prevent a number of functional declines associated with ageing. A minimum of 150 minutes a week at a moderate intensity physical activity such as brisk walking will result in numerous health benefits (Krucoff et al., 2010). These benefits include prevention of heart disease and colon cancer, mitigate the effects of chronic disease, improve coordination and flexibility to avoid falls, and alleviate depression (Goetzel et al., 2007). Adults who practice even simple physical activity can improve their health status and use few health and social services (Goetzel et al., 2007). Our healthcare system should be investing in programs to keeping our older adult population healthy and active in their lives.

The Canadian Medical Association agrees that older adults should have access to high-quality well-funded programs to help them achieve and maintain physical fitness, optimal nutrition, promotion of mental health, and reduction in social isolation (The Canadian Medical Association, 2015). In the province of British Columbia, there are many seniors based programs to keeping individuals active and healthy as they age. A project called Raising the Profile Project (RPP) is a senior project that provides support programs in health and wellness areas such as management of health conditions, affordable housing, nutritional supports – meal services, nutrition education, access to fresh fruits and vegetables, community gardens etc. (Raising the Profile Project, 2018). Information, referral, and advocacy services, which offer support on income benefit and support programs, housing services, health services, and community programs, are also provided. RPP provides education, recreation, and creative arts programs to provide an outlet for creativity, enhancing meaning in life and a sense of purpose (Raising the Profile Project, 2018). Seniors with a strong sense of purpose often live longer (Irving, Davis, & Collier, 2017). Raising the Profile project also offers a broad range of programming to support and promote physical activity, which is partially funded by the help of the Government of British Columbia’s Ministry of Health. Additional funding for RPP is provided by the United Way of the Lower Mainland, Vancity, Union of British Columbia Municipalities, and the City of Surrey (Raising the Profile Project, 2018). In Kamloops, where I live, there is a program called OnTrack. This program is offered through a partnership between the City of Kamloops and Interior Health, to support middle age and older individuals diagnosed with chronic illness to increase their participation in physical activity and receive support from others to better manage their condition (Raising the Profile Project, 2018).

One major problem with these senior programs is funding. British Columbia’s federal government provides some financial support to projects, yet they still require outside funding from other organizations. A study by Aldana (2001) reviewed 32 health promotion programs and found 28 that reported medical cost savings. Of the seven studies that calculated cost-benefit ratios, financial returns averaged $3.48 for every dollar expended. In a study by Fries and McShane (1998), the authors demonstrated that health promotion programs offered to seniors, can save between $101 to $648 per person a year on healthcare costs, depending upon who participates and how many programs they use. I believe the Canadian government should start budgeting for these types of programs and education in each province. These programs will help decrease healthcare expenditures and increase the quality of life of our growing older adult population.

In addition to providing high quality services for healthy ageing, accessibility to these services is crucial. For seniors who have multiple chronic diseases, care is complex. Our Canadian healthcare system should be flexible and responsive when caring for our older adult population. The future of Canadian healthcare should be delivered on a continuum for community based health care, for example: primary health care, chronic disease management programs, home care workers, long-term care and palliative care (HealthLink BC, 2018). This continuum should be managed so that the patient may remain at home, out of the hospital and long-term care as long as possible. It is crucial these individuals have easy access to the level of care they require in order to age healthily (The Canadian Medical Association, 2015). The healthcare continuum should also be offered for individuals in all cities across our provinces. Older adults should not have to drive to major centers to receive the care they require (Fries & McShane, 1998). In addition to the cost of driving to major centers, many of these healthcare services are not covered under the Canada Health Act, requiring out of pocket pay. Many seniors are on a limited income and cannot afford many extra expenses (Fries & McShane, 1998). I feel our government should develop an interdisciplinary health service to ensure older Canadians have access to physicians and multiple levels of care without costing them out of pocket. This type of investment will help decrease the healthcare expenditures related to hospital and physician visits, while increasing the overall quality of life in our population.

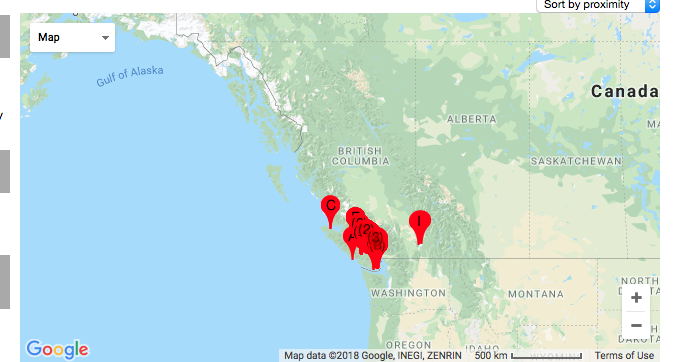

In British Columbia, the government website contains a seniors section that provides information in all areas such as healthy aging, health and safety, financial and legal matters, transportation, housing, home and community care. Many of the services stated on the website are covered by the federal government, such as senior’s services agency: island health – provides community-based outreach on the island to older adults with age-related mental health problems such as dementia and psychosis, depression, and addiction problems (HealthLink BC, 2018). There are senior contact programs in Kelowna, that offer brief daily phone calls to ensure the well-being and safety of seniors living alone. The federal government funds this service. Unfortunately, when looking for any type of senior program a majority of these services are around the Vancouver area with a few in Kelowna (HealthLink BC, 2018). This means that anyone living outside these areas do not have access to many senior programs.

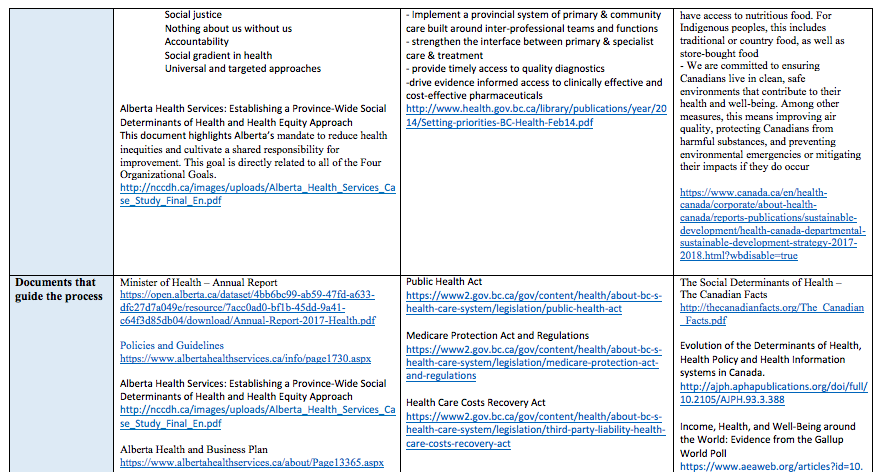

Figure 2. Depiction of where the majority of senior programs can be found throughout the province of British Columbia. – Vancouver, Vancouver Island, & Kelowna. Retrieved from https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/services-and-resources/find-services

I think in order for our healthcare system to advance, the government should prioritize both care and primary prevention for our older adult population. In 2017, the government provided funding to a number of national-level organizations to help improve care for seniors; including the Canadian Orthopaedic Foundation in collaboration with Bone and Joint Canada, and the Association of Canadian Community Colleges to develop national standards for personal support workers, and to a variety of research projects related to treating chronic diseases. Little funding was provided for support programs that involve primary prevention such as physical activity programs, or nutrition programs. In short, I think a focus on prevention and health promotion programs offers a promising approach to the urgent challenges that our healthcare is facing today and into the future.

What do you think about our Canadian healthcare system?

~Happy Blogging!~

Rachel

References

Aldana, S. (2001). Financial impact of health promotion programs: A comprehensive review of literature. American Journal of Health Promotion, 15(5), 296-320. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-15.5.296

Bruskas, D. (2008). Children in foster care: A vulnerable population at risk. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 21(2), 70-77. doi: 10.111/j1744-6171.2008.00134.x

CSEP. (2018). Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines. Retrieved from http://www.csep.ca/CMFiles/Guidelines/CSEP_PAGuidelines_older-adults_en.pdf

EuroHealthNet. (2018) Healthy ageing. Retrieved from http://www.healthyageing.eu/

Fries, J., & McShane, D. (1998). Reducing need and demand for medical services in high-risk persons. A health education approach. The Western Journal of Medicine, 169(4), 201-207. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1305287/

Goetzel, R., Shechter, D., Ozminkowski, R., Stapleton, D., Lapin, P., McGinnis, J., Gordon, C., & Breslow, L. (2007). Can health promotion programs save Medicare money? Clinical Interventions in Aging, 2(1), 117-122. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2684089/

Government of Canada. (2017). Action for senior’s report. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/seniors-action-report.html#tc6a

HealthLink BC. (2018). Services and resources. Retrieved from https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/services-and-resources/find-services

Irving, J., Davis, S., & Collier, A. (2017). Aging with purpose: A systematic search and review of literature pertaining to older adults and purpose. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 85(4), 403-437. doi: 10.1177/0091415017702908

Krucoff, C., Carson, K., Peterson, M., Shipp, K., & Krucoff, M. (2010). Teaching Yoga to seniors: Essential considerations to enhance safety and reduce risk in a uniquely vulnerable age group. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 16(8), 899-905. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0501

McPhee, J., French, D., Jackson, D., Nazroo, J., Pendleton, N., Degens, H. (2016). Physical activity in older age: Perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology,17, 567-580. doi: 10.1007/s10522-016-9641-0

Potter, P. & Perry, A. (2001). Fundamentals of nursing (5th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby, Inc.

Raising the Profile Project. (2018). Raising the profile. Retrieved from http://www.seniorsraisingtheprofile.ca/about/

Seniors First BC. (2018). Vulnerability. Retrieved from http://seniorsfirstbc.ca/for-professionals/vulnerability/

Statistics Canada. (2018). Seniors. Retrieved from https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-402x/2011000/chap/seniors-aines/seniors-aines-eng.htm

The Canadian Medical Association. (2015). A policy framework to guide a national seniors strategy for Canada. Retrieved from https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/about-us/gc2015/policy-framework-to-guide-seniors_en.pdf

The Canadian Medical Association. (2013). Health and health care for an aging population. Retrieved from https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/policy-research/CMA_Policy_Health_and_Health_Care_for_an_Aging-Population_PD14-03-e.pdf

Canada’s Healthcare System and Our Ageing Population

Rachel Parkinson

MHST 601

Athabasca University

Canada’s Healthcare System and Our Aging Population

What does it mean to be vulnerable? The word vulnerability describes an individual or a group of individuals at risk for poor physical, psychological, and social health as a result of barriers experienced by social, economical, political, and environmental resources (Bruskas, 2008). Vulnerable populations include; ethnic minorities, gender, social support, education level, income, genetic predisposition, and age such as children and seniors. As our communities grow, all vulnerable populations should be a priority for our healthcare system. Nonetheless, there is one population that is growing rapidly and requires immediate attention, our elderly population. Over the past 40 years, the proportion of senior population has grown from 8% to 14% in Canada. According to demographic projections, the proportion of seniors is expected to increase rapidly to between 23-25% of the total population by 2036 (Statistics Canada, 2018). What does this mean for the future of our healthcare system?

Currently Canadians over age 65 consume roughly 44% of provincial and territorial health care budgets, and the governments are concerned about the health care system’s capacity to provide quality of services in the future (The Canadian Medical Association, 2013). Although age does not automatically mean ill health or disability, the risk of both does increase with age. Age-related risk factors that influence one’s health include; decreased mobility, increased chronic disease, increased nutritional needs, financial decline related to retirement, and social isolation (Potter & Perry, 2001). Statistics Canada confirms that nearly three-quarters of Canadians over 65 years have at least one chronic health condition (The Canadian Medical Association, 2013). Statistics Canada also indicates that the Canadian healthcare system lacks resources to help older adults cope with these age-related risks. While these risk factors can have major affects on one’s quality of life, many of them can be managed and prevented. The key to providing optimal care for older adults begins with recognizing the risk factors then tailoring healthcare and educational programs towards this population (The Canadian Medical Association, 2013). I believe that in order to provide optimal care and support for Canada’s aging population, while trying to minimize pressure on the health-care system, governments at all levels should invest in programs to promote healthy ageing. As well, a comprehensive continuum of health services to provide optimal care and support.

Figure 1. Canada’s National Expenditures on Health in 2012 for each of the age groups. Retrieved from https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/policy-research/CMA_Policy_Health_and_Health_Care_for_an_Aging-Population_PD14-03-e.pdf

The Public Health Agency of Canada defines healthy ageing as a process of optimizing opportunities for physical, social, and mental health to enable seniors to take an active part in society and enjoy their lives (EuroHealthNet, 2018). It is understood that initiatives to promote healthy ageing will help lower the healthcare costs by reducing the number of hospital and physician visits due to disability and chronic disease (EuroHealthNet, 2018). Programs focused on physical activity, nutrition, and mental health will have a profound effect on individual quality of life, social support, physical health, and mental well-being. Despite the inevitable declines associated with age, research suggests the way in which older adults spent their final years, either in a nursing home, or living independently, may be greatly influenced by their physical activity habits throughout their life (Krucoff, Carson, Peterson, Shipp, & Krucoff, 2010). Participation in a regular physical activity is an effective way to reduce/prevent a number of functional declines associated with ageing. A minimum of 150 minutes a week at a moderate intensity physical activity such as brisk walking will result in numerous health benefits (Krucoff et al., 2010). These benefits include prevention of heart disease and colon cancer, mitigate the effects of chronic disease, improve coordination and flexibility to avoid falls, and alleviate depression (Goetzel et al., 2007). Adults who practice even simple physical activity can improve their health status and use few health and social services (Goetzel et al., 2007). Our healthcare system should be investing in programs to keeping our older adult population healthy and active in their lives.

The Canadian Medical Association agrees that older adults should have access to high-quality well-funded programs to help them achieve and maintain physical fitness, optimal nutrition, promotion of mental health, and reduction in social isolation (The Canadian Medical Association, 2015). In the province of British Columbia, there are many seniors based programs to keeping individuals active and healthy as they age. A project called Raising the Profile Project (RPP) is a senior project that provides support programs in health and wellness areas such as management of health conditions, affordable housing, nutritional supports – meal services, nutrition education, access to fresh fruits and vegetables, community gardens etc. (Raising the Profile Project, 2018). Information, referral, and advocacy services, which offer support on income benefit and support programs, housing services, health services, and community programs, are also provided. RPP provides education, recreation, and creative arts programs to provide an outlet for creativity, enhancing meaning in life and a sense of purpose (Raising the Profile Project, 2018). Seniors with a strong sense of purpose often live longer (Irving, Davis, & Collier, 2017). Raising the Profile project also offers a broad range of programming to support and promote physical activity, which is partially funded by the help of the Government of British Columbia’s Ministry of Health. Additional funding for RPP is provided by the United Way of the Lower Mainland, Vancity, Union of British Columbia Municipalities, and the City of Surrey (Raising the Profile Project, 2018). In Kamloops, where I live, there is a program called OnTrack. This program is offered through a partnership between the City of Kamloops and Interior Health, to support middle age and older individuals diagnosed with chronic illness to increase their participation in physical activity and receive support from others to better manage their condition (Raising the Profile Project, 2018).

One major problem with these senior programs is funding. British Columbia’s federal government provides some financial support to projects, yet they still require outside funding from other organizations. A study by Aldana (2001) reviewed 32 health promotion programs and found 28 that reported medical cost savings. Of the seven studies that calculated cost-benefit ratios, financial returns averaged $3.48 for every dollar expended. In a study by Fries and McShane (1998), the authors demonstrated that health promotion programs offered to seniors, can save between $101 to $648 per person a year on healthcare costs, depending upon who participates and how many programs they use. I believe the Canadian government should start budgeting for these types of programs and education in each province. These programs will help decrease healthcare expenditures and increase the quality of life of our growing older adult population.

In addition to providing high quality services for healthy ageing, accessibility to these services is crucial. For seniors who have multiple chronic diseases, care is complex. Our Canadian healthcare system should be flexible and responsive when caring for our older adult population. The future of Canadian healthcare should be delivered on a continuum for community based health care, for example: primary health care, chronic disease management programs, home care workers, long-term care and palliative care (HealthLink BC, 2018). This continuum should be managed so that the patient may remain at home, out of the hospital and long-term care as long as possible. It is crucial these individuals have easy access to the level of care they require in order to age healthily (The Canadian Medical Association, 2015). The healthcare continuum should also be offered for individuals in all cities across our provinces. Older adults should not have to drive to major centers to receive the care they require (Fries & McShane, 1998). In addition to the cost of driving to major centers, many of these healthcare services are not covered under the Canada Health Act, requiring out of pocket pay. Many seniors are on a limited income and cannot afford many extra expenses (Fries & McShane, 1998). I feel our government should develop an interdisciplinary health service to ensure older Canadians have access to physicians and multiple levels of care without costing them out of pocket. This type of investment will help decrease the healthcare expenditures related to hospital and physician visits, while increasing the overall quality of life in our population.

In British Columbia, the government website contains a seniors section that provides information in all areas such as healthy aging, health and safety, financial and legal matters, transportation, housing, home and community care. Many of the services stated on the website are covered by the federal government, such as senior’s services agency: island health – provides community-based outreach on the island to older adults with age-related mental health problems such as dementia and psychosis, depression, and addiction problems (HealthLink BC, 2018). There are senior contact programs in Kelowna, that offer brief daily phone calls to ensure the well-being and safety of seniors living alone. The federal government funds this service. Unfortunately, when looking for any type of senior program a majority of these services are around the Vancouver area with a few in Kelowna (HealthLink BC, 2018). This means that anyone living outside these areas do not have access to many senior programs.

Figure 2. Depiction of where the majority of senior programs can be found throughout the province of British Columbia. – Vancouver, Vancouver Island, & Kelowna. Retrieved from https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/services-and-resources/find-services

I think in order for our healthcare system to advance, the government should prioritize both care and primary prevention for our older adult population. In 2017, the government provided funding to a number of national-level organizations to help improve care for seniors; including the Canadian Orthopaedic Foundation in collaboration with Bone and Joint Canada, and the Association of Canadian Community Colleges to develop national standards for personal support workers, and to a variety of research projects related to treating chronic diseases. Little funding was provided for support programs that involve primary prevention such as physical activity programs, or nutrition programs. In short, I think a focus on prevention and health promotion programs offers a promising approach to the urgent challenges that our healthcare is facing today and into the future.

References

Aldana, S. (2001). Financial impact of health promotion programs: A comprehensive review of literature. American Journal of Health Promotion, 15(5), 296-320. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-15.5.296

Bruskas, D. (2008). Children in foster care: a vulnerable population at risk. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 21(2), 70-77. doi: 10.111/j1744-6171.2008.00134.x

CSEP. (2018). Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines. Retrieved from http://www.csep.ca/CMFiles/Guidelines/CSEP_PAGuidelines_older-adults_en.pdf

EuroHealthNet. (2018) Healthy Ageing. Retrieved from http://www.healthyageing.eu/

Fries, J., & McShane, D. (1998). Reducing need and demand for medical services in high-risk persons. A health education approach. The Western Journal of Medicine, 169(4), 201-207. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1305287/

Goetzel, R., Shechter, D., Ozminkowski, R., Stapleton, D., Lapin, P., McGinnis, J., Gordon, C., & Breslow, L. (2007). Can health promotion programs save Medicare money? Clinical Interventions in Aging, 2(1), 117-122. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2684089/

Government of Canada. (2017). Action for Senior’s Report. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/seniors-action-report.html#tc6a

HealthLink BC. (2018). Services & Resources. Retrieved from https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/services-and-resources/find-services

Irving, J., Davis, S., & Collier, A. (2017). Aging with purpose: a systematic search and review of literature pertaining to older adults and purpose. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 85(4), 403-437. doi: 10.1177/0091415017702908

Krucoff, C., Carson, K., Peterson, M., Shipp, K., & Krucoff, M. (2010). Teaching Yoga to seniors: essential considerations to enhance safety and reduce risk in a uniquely vulnerable age group. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 16(8), 899-905. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0501

McPhee, J., French, D., Jackson, D., Nazroo, J., Pendleton, N., Degens, H. (2016). Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology,17, 567-580. doi: 10.1007/s10522-016-9641-0

Potter, P. & Perry, A. (2001). Fundamentals of nursing (5th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby, Inc.

Raising the Profile Project. (2018). Retrieved from http://www.seniorsraisingtheprofile.ca/about/

Seniors First BC. (2018). Vulnerability. Retrieved from http://seniorsfirstbc.ca/for-professionals/vulnerability/

Statistics Canada. (2018). Seniors. Retrieved from https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-402-

x/2011000/chap/seniors-aines/seniors-aines-eng.htm

The Canadian Medical Association. (2015). A Policy Framework to Guide a National Seniors Strategy for Canada. Retrieved from https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/about-us/gc2015/policy-framework-to-guide-seniors_en.pdf

The Canadian Medical Association. (2013). Health and Health Care for an Aging Population. Retrieved from https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/policy-research/CMA_Policy_Health_and_Health_Care_for_an_Aging-Population_PD14-03-e.pdf

Canada’s Healthcare System and Our Ageing Population

Rachel Parkinson

MHST 601

Athabasca University

Canada’s Healthcare System and Our Aging Population

What does it mean to be vulnerable? The word vulnerability describes an individual or a group of individuals at risk for poor physical, psychological, and social health as a result of barriers experienced by social, economical, political, and environmental resources (Bruskas, 2008). Vulnerable populations include; ethnic minorities, gender, social support, education level, income, genetic predisposition, and age such as children and seniors. As our communities grow, all vulnerable populations should be a priority for our healthcare system. Nonetheless, there is one population that is growing rapidly and requires immediate attention, our elderly population. Over the past 40 years, the proportion of senior population has grown from 8% to 14% in Canada. According to demographic projections, the proportion of seniors is expected to increase rapidly to between 23-25% of the total population by 2036 (Statistics Canada, 2018). What does this mean for the future of our healthcare system?

Currently Canadians over age 65 consume roughly 44% of provincial and territorial health care budgets, and the governments are concerned about the health care system’s capacity to provide quality of services in the future (The Canadian Medical Association, 2013). Although age does not automatically mean ill health or disability, the risk of both does increase with age. Age-related risk factors that influence one’s health include; decreased mobility, increased chronic disease, increased nutritional needs, financial decline related to retirement, and social isolation (Potter & Perry, 2001). Statistics Canada confirms that nearly three-quarters of Canadians over 65 years have at least one chronic health condition (The Canadian Medical Association, 2013). Statistics Canada also indicates that the Canadian healthcare system lacks resources to help older adults cope with these age-related risks. While these risk factors can have major affects on one’s quality of life, many of them can be managed and prevented. The key to providing optimal care for older adults begins with recognizing the risk factors then tailoring healthcare and educational programs towards this population (The Canadian Medical Association, 2013). I believe that in order to provide optimal care and support for Canada’s aging population, while trying to minimize pressure on the health-care system, governments at all levels should invest in programs to promote healthy ageing. As well, a comprehensive continuum of health services to provide optimal care and support.

Figure 1. Canada’s National Expenditures on Health in 2012 for each of the age groups. Retrieved from https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/policy-research/CMA_Policy_Health_and_Health_Care_for_an_Aging-Population_PD14-03-e.pdf

The Public Health Agency of Canada defines healthy ageing as a process of optimizing opportunities for physical, social, and mental health to enable seniors to take an active part in society and enjoy their lives (EuroHealthNet, 2018). It is understood that initiatives to promote healthy ageing will help lower the healthcare costs by reducing the number of hospital and physician visits due to disability and chronic disease (EuroHealthNet, 2018). Programs focused on physical activity, nutrition, and mental health will have a profound effect on individual quality of life, social support, physical health, and mental well-being. Despite the inevitable declines associated with age, research suggests the way in which older adults spent their final years, either in a nursing home, or living independently, may be greatly influenced by their physical activity habits throughout their life (Krucoff, Carson, Peterson, Shipp, & Krucoff, 2010). Participation in a regular physical activity is an effective way to reduce/prevent a number of functional declines associated with ageing. A minimum of 150 minutes a week at a moderate intensity physical activity such as brisk walking will result in numerous health benefits (Krucoff et al., 2010). These benefits include prevention of heart disease and colon cancer, mitigate the effects of chronic disease, improve coordination and flexibility to avoid falls, and alleviate depression (Goetzel et al., 2007). Adults who practice even simple physical activity can improve their health status and use few health and social services (Goetzel et al., 2007). Our healthcare system should be investing in programs to keeping our older adult population healthy and active in their lives.

The Canadian Medical Association agrees that older adults should have access to high-quality well-funded programs to help them achieve and maintain physical fitness, optimal nutrition, promotion of mental health, and reduction in social isolation (The Canadian Medical Association, 2015). In the province of British Columbia, there are many seniors based programs to keeping individuals active and healthy as they age. A project called Raising the Profile Project (RPP) is a senior project that provides support programs in health and wellness areas such as management of health conditions, affordable housing, nutritional supports – meal services, nutrition education, access to fresh fruits and vegetables, community gardens etc. (Raising the Profile Project, 2018). Information, referral, and advocacy services, which offer support on income benefit and support programs, housing services, health services, and community programs, are also provided. RPP provides education, recreation, and creative arts programs to provide an outlet for creativity, enhancing meaning in life and a sense of purpose (Raising the Profile Project, 2018). Seniors with a strong sense of purpose often live longer (Irving, Davis, & Collier, 2017). Raising the Profile project also offers a broad range of programming to support and promote physical activity, which is partially funded by the help of the Government of British Columbia’s Ministry of Health. Additional funding for RPP is provided by the United Way of the Lower Mainland, Vancity, Union of British Columbia Municipalities, and the City of Surrey (Raising the Profile Project, 2018). In Kamloops, where I live, there is a program called OnTrack. This program is offered through a partnership between the City of Kamloops and Interior Health, to support middle age and older individuals diagnosed with chronic illness to increase their participation in physical activity and receive support from others to better manage their condition (Raising the Profile Project, 2018).

One major problem with these senior programs is funding. British Columbia’s federal government provides some financial support to projects, yet they still require outside funding from other organizations. A study by Aldana (2001) reviewed 32 health promotion programs and found 28 that reported medical cost savings. Of the seven studies that calculated cost-benefit ratios, financial returns averaged $3.48 for every dollar expended. In a study by Fries and McShane (1998), the authors demonstrated that health promotion programs offered to seniors, can save between $101 to $648 per person a year on healthcare costs, depending upon who participates and how many programs they use. I believe the Canadian government should start budgeting for these types of programs and education in each province. These programs will help decrease healthcare expenditures and increase the quality of life of our growing older adult population.

In addition to providing high quality services for healthy ageing, accessibility to these services is crucial. For seniors who have multiple chronic diseases, care is complex. Our Canadian healthcare system should be flexible and responsive when caring for our older adult population. The future of Canadian healthcare should be delivered on a continuum for community based health care, for example: primary health care, chronic disease management programs, home care workers, long-term care and palliative care (HealthLink BC, 2018). This continuum should be managed so that the patient may remain at home, out of the hospital and long-term care as long as possible. It is crucial these individuals have easy access to the level of care they require in order to age healthily (The Canadian Medical Association, 2015). The healthcare continuum should also be offered for individuals in all cities across our provinces. Older adults should not have to drive to major centers to receive the care they require (Fries & McShane, 1998). In addition to the cost of driving to major centers, many of these healthcare services are not covered under the Canada Health Act, requiring out of pocket pay. Many seniors are on a limited income and cannot afford many extra expenses (Fries & McShane, 1998). I feel our government should develop an interdisciplinary health service to ensure older Canadians have access to physicians and multiple levels of care without costing them out of pocket. This type of investment will help decrease the healthcare expenditures related to hospital and physician visits, while increasing the overall quality of life in our population.

In British Columbia, the government website contains a seniors section that provides information in all areas such as healthy aging, health and safety, financial and legal matters, transportation, housing, home and community care. Many of the services stated on the website are covered by the federal government, such as senior’s services agency: island health – provides community-based outreach on the island to older adults with age-related mental health problems such as dementia and psychosis, depression, and addiction problems (HealthLink BC, 2018). There are senior contact programs in Kelowna, that offer brief daily phone calls to ensure the well-being and safety of seniors living alone. The federal government funds this service. Unfortunately, when looking for any type of senior program a majority of these services are around the Vancouver area with a few in Kelowna (HealthLink BC, 2018). This means that anyone living outside these areas do not have access to many senior programs.

Figure 2. Depiction of where the majority of senior programs can be found throughout the province of British Columbia. – Vancouver, Vancouver Island, & Kelowna. Retrieved from https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/services-and-resources/find-services

I think in order for our healthcare system to advance, the government should prioritize both care and primary prevention for our older adult population. In 2017, the government provided funding to a number of national-level organizations to help improve care for seniors; including the Canadian Orthopaedic Foundation in collaboration with Bone and Joint Canada, and the Association of Canadian Community Colleges to develop national standards for personal support workers, and to a variety of research projects related to treating chronic diseases. Little funding was provided for support programs that involve primary prevention such as physical activity programs, or nutrition programs. In short, I think a focus on prevention and health promotion programs offers a promising approach to the urgent challenges that our healthcare is facing today and into the future.

References

Aldana, S. (2001). Financial impact of health promotion programs: A comprehensive review of literature. American Journal of Health Promotion, 15(5), 296-320. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-15.5.296

Bruskas, D. (2008). Children in foster care: a vulnerable population at risk. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 21(2), 70-77. doi: 10.111/j1744-6171.2008.00134.x

CSEP. (2018). Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines. Retrieved from http://www.csep.ca/CMFiles/Guidelines/CSEP_PAGuidelines_older-adults_en.pdf

EuroHealthNet. (2018) Healthy Ageing. Retrieved from http://www.healthyageing.eu/

Fries, J., & McShane, D. (1998). Reducing need and demand for medical services in high-risk persons. A health education approach. The Western Journal of Medicine, 169(4), 201-207. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1305287/

Goetzel, R., Shechter, D., Ozminkowski, R., Stapleton, D., Lapin, P., McGinnis, J., Gordon, C., & Breslow, L. (2007). Can health promotion programs save Medicare money? Clinical Interventions in Aging, 2(1), 117-122. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2684089/

Government of Canada. (2017). Action for Senior’s Report. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/programs/seniors-action-report.html#tc6a

HealthLink BC. (2018). Services & Resources. Retrieved from https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/services-and-resources/find-services

Irving, J., Davis, S., & Collier, A. (2017). Aging with purpose: a systematic search and review of literature pertaining to older adults and purpose. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 85(4), 403-437. doi: 10.1177/0091415017702908

Krucoff, C., Carson, K., Peterson, M., Shipp, K., & Krucoff, M. (2010). Teaching Yoga to seniors: essential considerations to enhance safety and reduce risk in a uniquely vulnerable age group. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 16(8), 899-905. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0501

McPhee, J., French, D., Jackson, D., Nazroo, J., Pendleton, N., Degens, H. (2016). Physical activity in older age: perspectives for healthy ageing and frailty. Biogerontology,17, 567-580. doi: 10.1007/s10522-016-9641-0

Potter, P. & Perry, A. (2001). Fundamentals of nursing (5th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby, Inc.

Raising the Profile Project. (2018). Retrieved from http://www.seniorsraisingtheprofile.ca/about/

Seniors First BC. (2018). Vulnerability. Retrieved from http://seniorsfirstbc.ca/for-professionals/vulnerability/

Statistics Canada. (2018). Seniors. Retrieved from https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-402-

x/2011000/chap/seniors-aines/seniors-aines-eng.htm

The Canadian Medical Association. (2015). A Policy Framework to Guide a National Seniors Strategy for Canada. Retrieved from https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/about-us/gc2015/policy-framework-to-guide-seniors_en.pdf

The Canadian Medical Association. (2013). Health and Health Care for an Aging Population. Retrieved from https://www.cma.ca/Assets/assets-library/document/en/advocacy/policy-research/CMA_Policy_Health_and_Health_Care_for_an_Aging-Population_PD14-03-e.pdf